Cinematic Storytelling:

Escape From New York (1981)

I’m not going into the movie itself. What can I say about the movie that many other people have said about this highly enjoyable and fun movie? I also wrote about John Carpenter’s output as a musician in this post.

Rather, I want into the magic of making what went into making a film like Escape From New York.

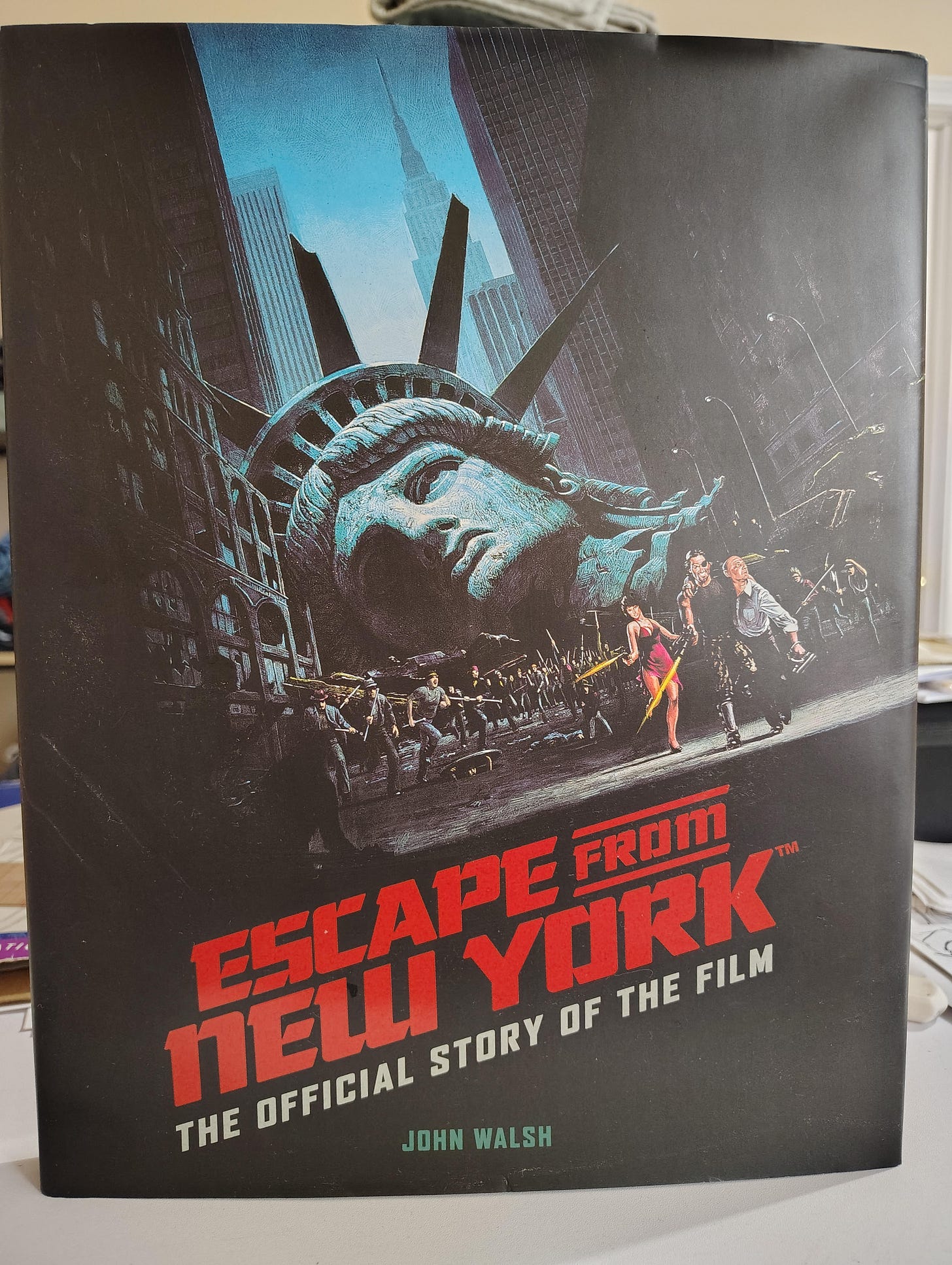

I recently acquired a book that chronicles the making of Escape From New York, by John Walsh.

The cover to John Walsh’s coffee-table sized compressed pack of enjoyment. If you’re a fan of the movie this book will be a nice compliment to the collected media you have about the movie.

This is more than a book. It’s a bundle of enjoyment for those who love to know how Things Are Made. Through behind-the-scenes photos (digital transfers from 35 mm prints), writes ups and quotes from those involved (including Carpenter and Russell themselves, among others) we are treated to the closest tech we have to traveling back in time.

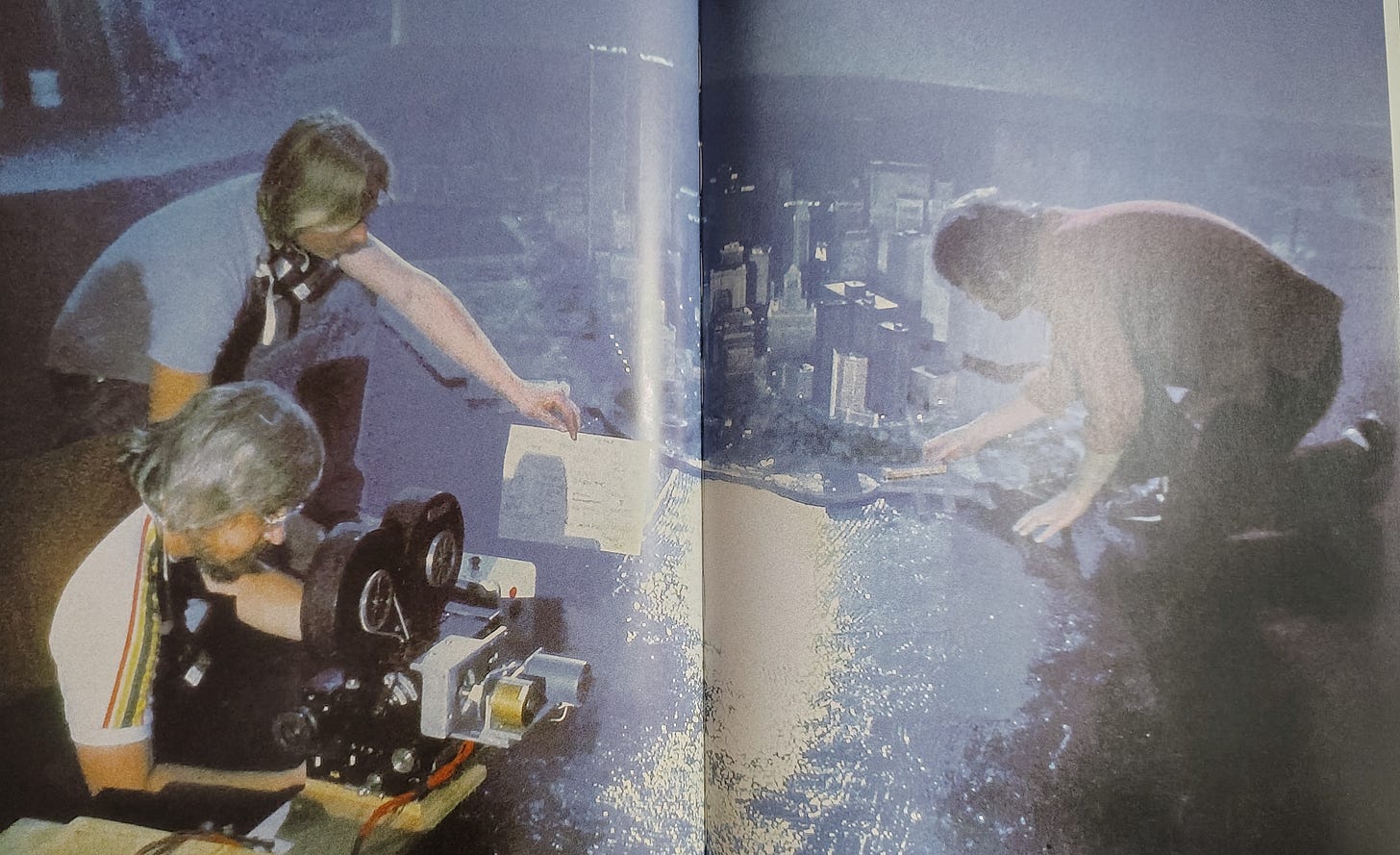

This book takes you back to a time when visual effects were created with models, and big, bulky multi-pass optical printers, and reverse film stock that required a very specific lighting set up, and other techniques that often were innovated at the moment. Because they couldn’t anticipate every technical and creative problem that would come their way, and the action had to be captured on-camera.

The New York skyline is recreated in a scale model to film Snake’s POV as he flies the hang glider into Manhattan to rescue the President. It’s staggering to think of the amount of effort required to build this, to then film what amounts to a few seconds of film in the final cut of the movie.

This book also reflects one of the problems with modern filmmaking: an overreliance on technology and a lack of creative thinking in that outside-the-box sort of way. The dominant thought is something like, “Because everything can be done, let’s throw everything at the audience and show them how amazing we are!”

But this is misguided thinking. It doesn’t start from the question “What is necessary to show the audience here?” That is egocentric thinking that is more interested in impressing the audience than making them feel something.

Less can be more when it comes to visual storytelling. Show the necessary elements to allow the viewers to connect them in their minds in a way that adds up to something greater. SYNERGY.

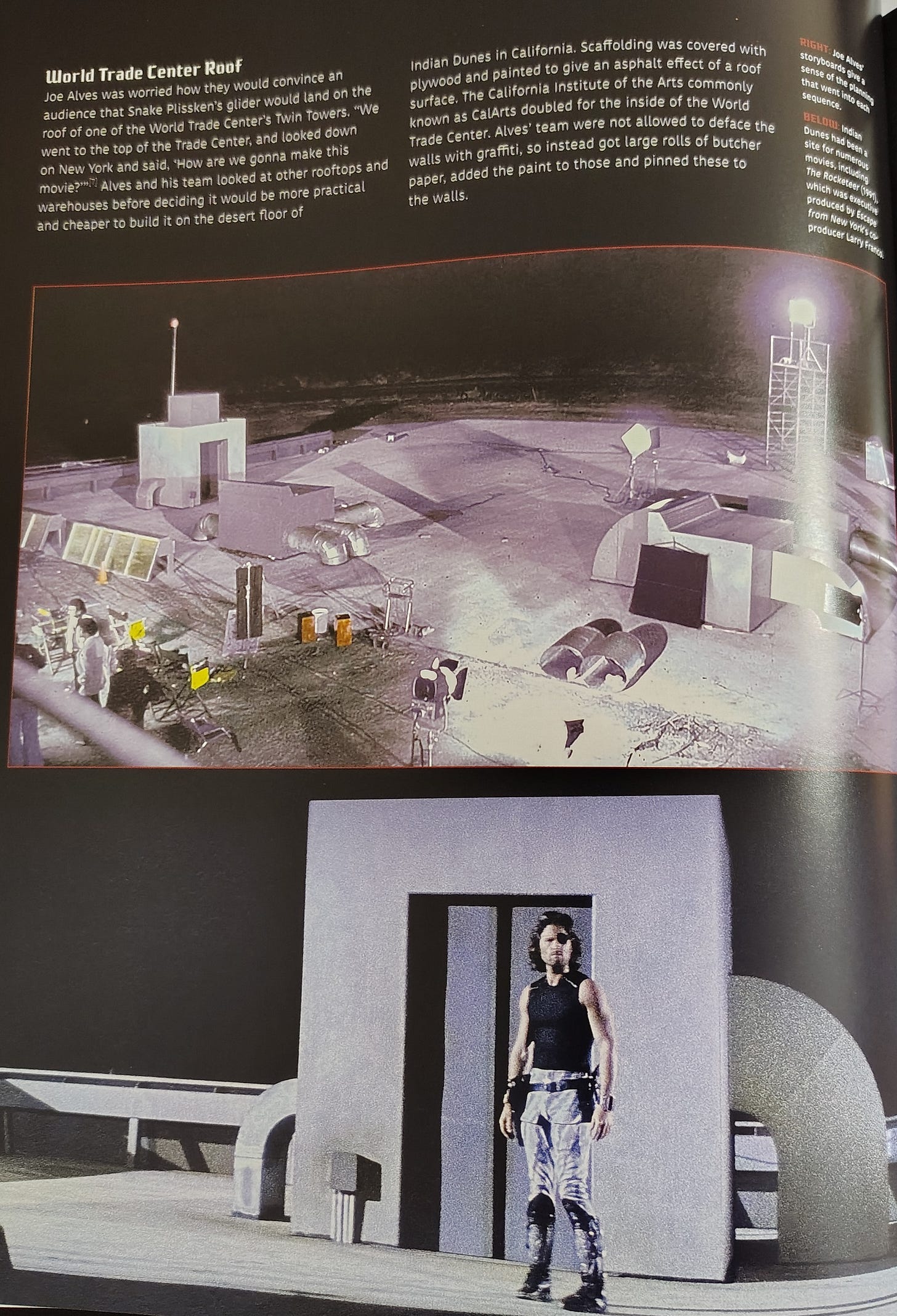

This synergy came through in the hands-on filmmaking as well. It was very much a team effort where the input of other experts had to be factored into directorial decisions. While the director was making on the set with the actors, technicians were making sets and staging actions elsewhere, such as in this shot where Snake’s landing on the rooftop of the World Trade Center was staged and shot in the California desert.

This is movie magic. A kind of magic that takes endurance, patience, and discipline to see it through to the other end as a finished movie.

In many ways, endurance and endless patience may be far better qualities in a filmmaker than a high level of technical knowledge, or creativity. I can’t imagine the headache it must have been to keep so many subsets of a film project straight, but John Carpenter managed it gracefully, and gave us that are combination of a film that is both a crowd pleaser and a cult classic that with time has become a symbol of movie magic. (Not to take away from visual effects creators. What they do is impressive and necessary, but it doesn’t have that sense of wonder and excitement that practical effect filmmaking has. Recreating that joyful sensation of playing with big toys as an adult while recreating the stories you made up with your GI Joe action figures when you were little.)

And though his name is on the film as director, there is no ego in Carpenter in recognizing the contributions of the many people it took for Escape to be the film we know and love.

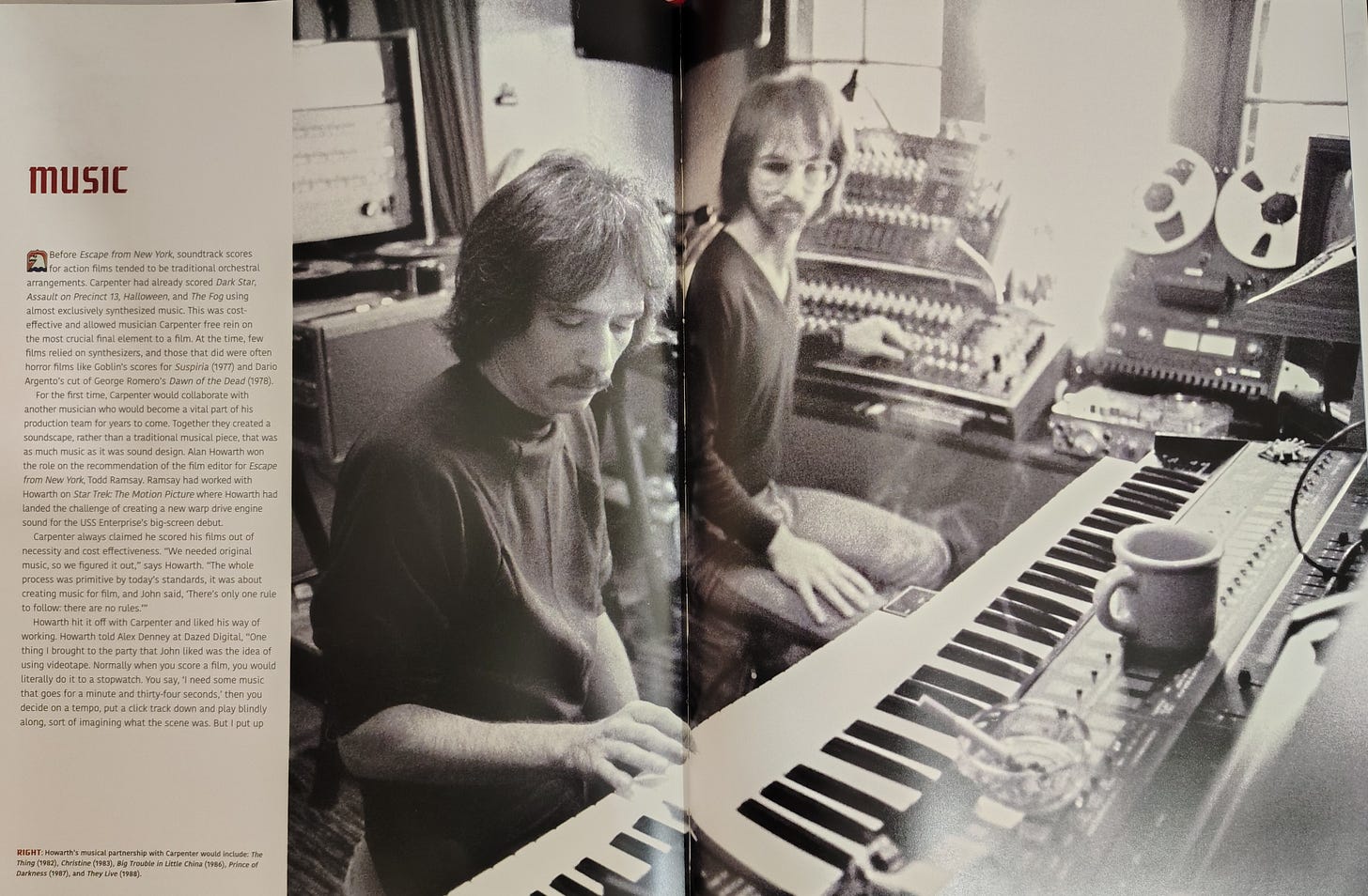

That synergy of collaboration is something that carried over past the time when the shooting stopped and into the editing and composing. You can see John Carpenter with musical partner Alan Howarth, crafting the now iconic theme of Escape From New York.

Cigarettes and coffee. The best inspiration jumpstarters.

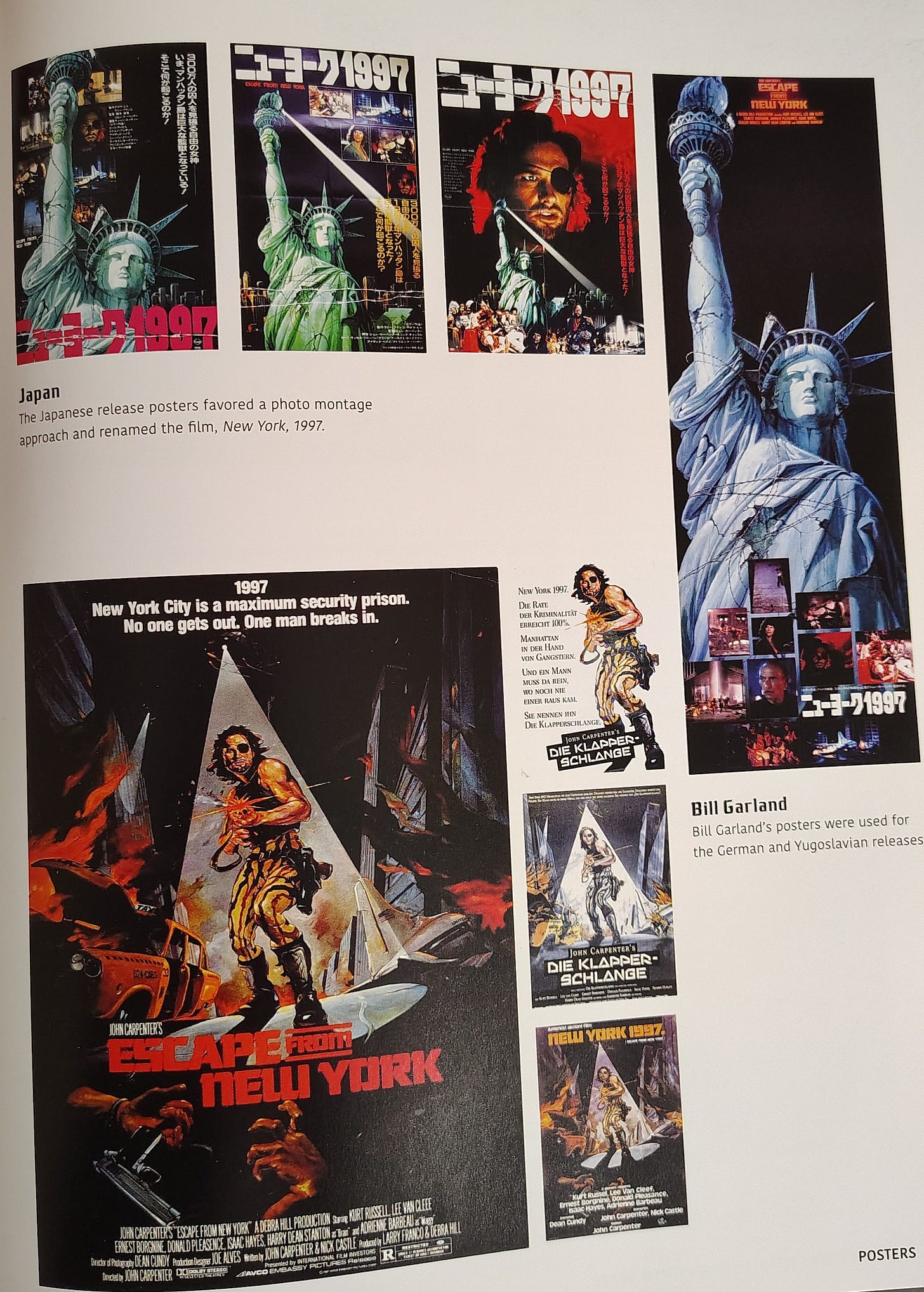

And this synergy goes on through to marketing, where multiple approaches were tried and discarded in the art that went towards advertising the film.

Snake Plissken is called Snake Plissken everywhere in the world, except in Italy where for some reason he became Hyena.

This type of filmmaking hasn’t entirely left us, but it’s become a type of privilege for filmmakers who have the box office clout and eccentricity to demand it.

But a sense of partnership and collaboration can be brought to anything you do with digital tools today.

"an overreliance on technology and a lack of creative thinking in that outside-the-box sort of way." - yes indeed, Jay.

The cigarettes and coffee photo says everything about the difference between then and now. Today's composers have infinite sounds at their fingertips, but Carpenter and Howarth created something iconic with just synthesizers and pure collaboration.

As a scriptwriter myself, good writing like this film is excellent research.

As an Animator from before the computer age, I love practical effects.

I also think Hollydumb for not appreciating Carpenter.